S1E8: Suffering Witches to Live: Jewish Women and the Legacies of Religious Law

With Dr. Elizabeth Shanks Alexander

Dr. Elizabeth Shanks Alexander teaches us rabbinic laws about women, how to make sense of gendered commands in Judaism, and the famous “positive, timebound commandments.” Meet the woman who led a synagogue, the woman who issued her own legal rulings, and the businesswoman who fled a war.

We also ask, can women can keep track of their own periods? How was religious law as a boys’ club? And why did ancient rabbis care so much about witchery (or did they)?

“The rabbis are…saying, sometimes scripture genders things not because of legal consequences but as a reflection of how human society conducts itself.”

BIO

Dr. Elizabeth Shanks Alexander is Full Professor at the University of Virginia in the Department of Religious Studies. She received her MA, Phil, and PhD in Judaic Studies all from Yale University, after a BA in Religion from Haverford College. She has written extensively about rabbinic literature and culture, especially oral tradition and the production of the Mishnah. In the last decade she has turned her attention to women, ritual, and gender within rabbinic literature. Her book Gender and Timebound Commandments in Judaism (2013) was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. She has also published Transmitting Mishnah: The Shaping Influence of Oral Tradition(2006). Her current project explores the rabbinic gendering of biblical Israel.

-

[podcast theme music begins – an upbeat, Mediterranean-sounding detective vibe]

Emily Chesley: Welcome to Women Who Went Before, a gynocentric quest into the ancient world! I’m Emily Chesley…

Rebekah Haigh: …and I’m Rebekah Haigh…

Emily: …scholars, friends, and fellow text-raiders!

[theme music continues, then bounces out]

Rebekah: In today’s episode, “Suffering Witches to Live: Jewish Women and the Legacies of Religious Law,” we talk with Dr. Elizabeth Shanks Alexander about whether women can keep track of their own periods, religious law as a boys’ club, and why ancient rabbis cared so much about witchery.

[podcast music theme music enters in]

Emily: On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, the future US president, to advocate for greater legal rights for women in a new code of American laws. She asked, “I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could…”[1] Despite her fervent petition, women were excluded as citizens. It would be 150 years before the 19th Amendment gave American women the right to vote.

Rebekah: Everyone understands that men were the primary legislators in the ancient world, as they were in America, inevitably making women more legally vulnerable. However, among ancient Jewish communities, political (that is to say, imperial) laws were supplemented by a vast corpus of religious laws issued by rabbis and sages.

As you might expect, these laws regulated religious rituals and commented on theological issues. Like what to do when you’re traveling and the Sabbath evening falls (Shabbath 153a). The rabbis were interested in what taboos must be avoided, how to perform specific rituals, and how to interpret earlier legal traditions, including the Torah. But since obedience to God was seen as infiltrating every part of one’s life, rabbinic laws also commented on spheres that today might appear as secular (e.g., Bava Metzia 83b and Mishnah Bava Metzia 8).

Emily: Scholars trace these Jewish religious traditions through several large collections of laws that commented on and interpreted the Torah, or biblical law. The first collection of texts are the Mishnah and the Tosefta. Produced during the Tannaitic period (roughly 70–250 CE) in Roman Palestine, this earliest generation of rabbinic sages were, naturally, known as the tannaim. Each collection of laws then became the object of centuries of more interpretation as rabbis applied old laws to new contexts and addressed issues that hadn’t been resolved previously. So for instance the Palestinian and Babylonian Talmuds, written in the 4th century CE and those that followed, commented on and re-interpreted the earlier material in the Mishnah and Tosefta.

Rebekah: Roman laws like those we talked about with Thomas McGinn, could be enforced by the state. But rabbinic laws, especially in the Tannaitic period, were written by religious leaders who lacked practical institutional power to realize their ideals. The Jewish temple had just been destroyed and the Jewish state dismantled. In fact, many of the laws we find in the Mishnah or the Talmud belong to the realm of wishful thinking. The rabbinic laws thus tell us less about “real women” and more about what preoccupied a small, all-boys club of Jewish sages in antiquity. Though as Sarit Kattan Gribetz reminds us in Episode 1, there may have been a handful of exceptions.

Emily: Even when rabbinic law could be implemented, it didn’t automatically mean that it was – or at least not right away and not by everyone. According to the Mishnah, Rabbi Eliezer argued that “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah is teaching her promiscuity” (m.Sotah 3:4). That seems pretty straightforward. Women cannot study Torah.

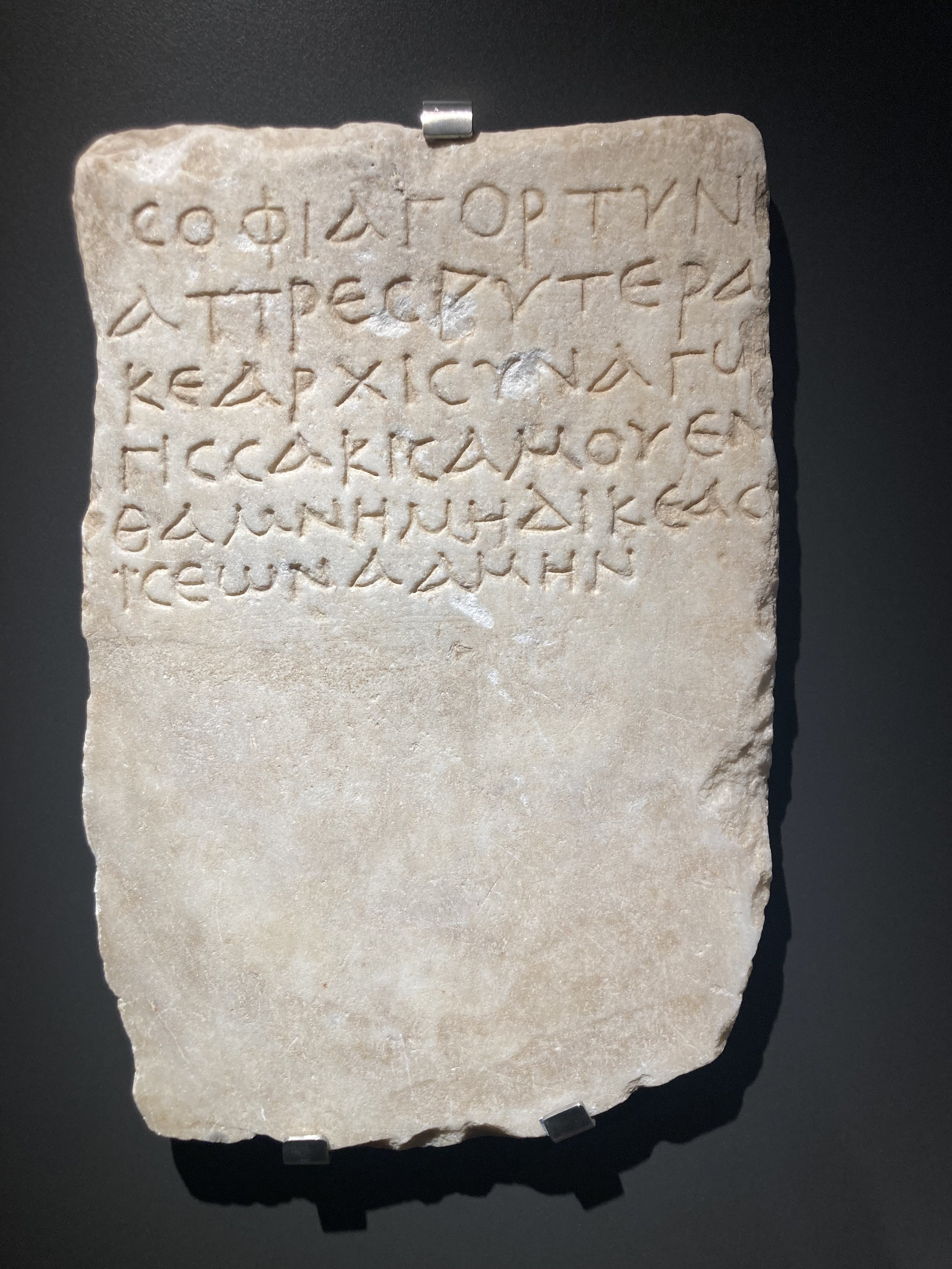

But surprisingly, a third-century funerary inscription from Smyrna (modern-day İzmir, Turkey), names a woman Rufina as the head of a synagogue: an archisynagogos (ἀρχισυνάγωγος).[2] While we can’t assume Rufina was a literate Torah scholar, we also shouldn’t assume she couldn’t have been or that her title archisynagogos was merely a fancy way of calling her a wealthy donor.[3]

So should we take at face value those rabbinic rulings that limited female obligation to Torah study and regulated women to the domestic sphere?

Rebekah: Figuring out how to glimpse lived reality behind these laws is notoriously complex, and scholars disagree over whether or not it’s even possible. As an example, let’s look at a pernicious cliche: the witch. Across ancient Mesopotamia a number of peoples seem to have held a stereotype that women were more prone to witchery and nefarious magic. Examining records of ancient Akkadian legal proceedings, scholars Tzvi Abusch and Daniel Schwemer found that the only known persons accused of witchcraft were women.[4]

Emily: The Hebrew Bible took a hard line against all forms of magic and divination. Exodus 22:18 says, in the famous translation of the King James Bible: “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” “Witch” specifically meaning “woman” here.

Centuries later, the biblical laws against witchcraft became sites of commentary by the rabbis. Hillel links women especially with witchcraft in the Mishnah, when he says, “The more wives, the more witchcraft. The more female slaves, the more carnality” (Pirkei Avot 2:7, trans. Haigh). The Palestinian Talmud sites a story of Shimon ben Shetach, saying that he hanged 80 witches in Ashkelon in the first century BCE. (y. Sanh. 6.6, 23c; y. Hag. 2.2. 77d). They were said to live in a cave and harm the world with their magic. But whoever edited the Palestinian Talmud 500 years later, viewed witch hunts as a plausible legal action – something that could be done given the right circumstances.[5]

Rebekah: On the one hand, the Hebrew Bible and the dutifully-following rabbis recognized women as potentially susceptible when it came to magic.[6] As their contemporaries did. On the other hand, plenty of other parts of the Bible and the rabbinic corpus warn against anyone male and female practicing things like necromancy, divination or suspicious activities that were deemed magic. (And of course, if the right person was doing it in the right way, it wasn’t magic at all!) So how to read Shimon ben Shetach? Anyone could perform bad magic in theory, but women in social-literary imagination were believed more likely to do so.

Emily: Later rabbis’ assumptions also colored the way they interpreted and revised earlier laws. Scholar Tal Ilan calls this phenomenon censorship.[7] In the Tosefta, for instance, a woman named Beruriah briefly unsettles an otherwise all-male cast of rabbis by offering her own legal ruling (T. Keilim Bava Metzia 1.3).[8] Something a woman would normally never be permitted to do. But Beruriah vanishes from the Mishnah’s version of this ruling (M. Kelim 11:4). Later rabbis censored her from the story.

Rebekah: Much like studying the Torah, some obligations belonged firmly to the domain of fathers and sons, and rabbis and disciples. In the Mishnah, the rabbis exempted women from what scholars call “positive timebound commandments.” As you’ll remember from Episode 1, positive commandments are orders to do things, unlike negative commandments which are orders not to do things. Probably the most famous positive commandment is, “Love the Lord your God” (Deut 6:5). Most positive commandments applied to women equally as to men, to children as much as adults. Everyone was supposed to honor their father and mother.

Emily: But a few particular commandments had to be performed at specific times of the day or year. Praying the Shema at certain intervals during the day. Wearing tefillin (or, phylacteries) during the day but not at night.[9] For commandments like these, when you did them mattered. In the Mishnah and the Talmud, such positive time-specific commandments were not required of women (M Kiddushin 1:7; B.Kiddushin 29a). Some scholars have proposed a rationale for why the rabbis made this distinction: that mothers and wives could not expect their time to be their own.[10] And a baby needs to be fed when it’s hungry, not necessarily at a time that conveniently avoids a Sabbath service.

The literature the early rabbis produced does not provide us a direct portal into the realities of the past, to Jewish life in antiquity. Instead, this legal corpus represents an ongoing project that created a masculinist, rabbinic version of Jewish culture. Even if these rulings were not necessarily enforced and practiced, they still tell us a great deal about the men who wrote them—about their perceptions of women and fears about them, about the sexual dangers they imagined lurking in women’s bodies, and about the lack of trust men had for women.

Rebekah: Our guest is Dr. Elizabeth Shanks Alexander, a Professor at the University of Virginia in the Department of Religious Studies. She received her PhD in Judaic Studies from Yale University. She has written extensively about rabbinic literature and culture, especially oral tradition and the production of the Mishnah. In the last decade, she has turned her attention to women, ritual, and gender within rabbinic literature. Her book Gender and Timebound Commandments in Judaism (2013) was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. And her current project explores the rabbinic gendering of biblical Israel. We are delighted to have her on the podcast!

[musical interlude]

Rebekah: So let’s start with the timebound positive commandments that you’ve written about in the past. As I understand it, the Mishnah obligates men to perform all the commandments of Torah, but women are exempt from the “timebound,” “positive” commandments (Mishnah Kiddushim 1:7). So can you flesh out this legal distinction for our audience, and maybe talk about the differing roles that men and women had according to rabbinic law?

Elizabeth Shanks Alexander (Liz): The first thing I want to note is actually that the distinction between timebound commandments and non timebound commandments appears very infrequently in the Mishnah, which is this early stratum of rabbinic law. And there’s never a reason given for why women are exempt from this particular category of commandments.

But it has become a lightning rod in the modern period for stabilizing gender roles in Judaism. So if you want to know what is the ideal model of Jewish womanhood, you go straight to this rule from the Mishnah. And you try to find an explanation.

So you say, [describing a common approach] “Well, okay, the rule says men are obligated in all the commandments; women are obligated in all the commandments except the timebound commandments. So what that means then, is that the difference between men and women somehow turns on this idea of timeboundedness, and so from there we can postulate all kinds of things about what quote ‘the proper role for women’ is. A ritual obligation ties you down to something that needs to be done at a certain time.”

So the first thing that I would say in answer to your question, is that the reason contemporary modern scholars are interested in this rule is because it seemed to have so much explaining power. So every scholar and their sister [all chuckle] wanted to explain, you know, what’s the reason that women are exempt from timebound commandments? We don’t have our first explanations of why women are exempt until the medieval period. That’s kind of interesting.

Actually if you go down back to the original, the earliest list of timebound commandments, the prototypical timebound commandment is tefillin. In antiquity the tefillin— There’s some wonderful, wonderful examples that were found at the Dead Sea site of Qumran. And what they consist of is a scroll that has, with teeny tiny writing, really about 2 to 4 centimeters long, just a centimeter wide. So these scrolls have key biblical texts written them, and they are rolled up in a tiny, tiny little bound thing, tied, and then put into these leather cases. And those would have been worn, according to rabbinic tradition, all day and taken off at night.

So that is the quintessential timebound commandment—something that you wear during the day but not at night. And so you can see how the idea of timeboundedness might have gotten connected to something that has to be, I got to get to morning prayers and the morning prayers are in the synagogue, not at home where the kid is pulling on the apron strings. But that’s not at all a reflection.

Another example of a time bound commandment is the commandment of tzitzit, or fringes. These are the obligation to put fringes on the corner of your garments so that you recall so that your eyes stay focused on your covenantal obligations and you don’t stray after foreign gods. And these tzitzit are also, one is obligated to wear them during the day and not at night, so those are also timebound.

Rebekah: What about the obligation to study Torah? How does that play out in terms of this conversation about what men are supposed to do and what women are not obligated to do?

Liz: What’s really interesting is that the study of Torah is not timebound at all, and so it actually has no formal place in this network of timebound commandments. However, when the earliest rabbinic sources ask why women are exempt from tefillin—that is, from those phylacteries, they’re almost like amulets which have little things of scripture inside of them—the answer that they give is because tefillin accomplishes the same thing that Torah study accomplishes.

The way that I understand this is that tefillin is a way of internalizing, embodying, taking scripture into the self. And Torah study also is a way of embodying scripture, taking scripture into the self.

And so if I were to sort of say, what do I think is the key law that distinct that really stabilizes gender difference? It’s nothing. The timebound commandment, that’s a red herring. And you know, we got caught up in that because of how things got transmitted and different meanings that accrued throughout history.

But if you want to think about rabbinic tradition and where is the crux of what distinguishes men’s roles and women’s roles, I would say that that revolves around the obligation or the lack of obligation or the she-shouldn’t-at-all obligation of Torah study. And that’s actually another question. Which is, it says in some places it says women are exempt from Torah study, but in other places the implication seems to be they are prohibited from Torah study. So that’s another can of worms.

Rebekah: And that’s not the same thing at all. [laughs]

Liz: No it’s not.

Emily: We’ve already touched on this. You mentioned earlier the ideal Jewish woman, ideal Jewish womanhood. How did the rabbis understand ideal Jewish womanhood? Did female piety differ from male piety?

Liz: Oh, I think female piety differed significantly from male piety. To be honest, I don’t think we know very much about female piety from rabbinic sources. Rabbinic sources are interested in rabbinic men. [laughs] In rabbis, go figure.

Rebekah: [wryly] So shocking.

Liz: And they extend a lot of energy thinking about male piety, so rabbinic piety. And I think they also expend a certain amount of energy thinking about how do you layify? [chuckles] In other words, how do you transmit to the laity a very elite notion of rabbinic piety?

So one of the other rituals that is not actually described as a timebound commandment in the earliest source is the Shema, the recitation of the Shema, which is the recitation of certain biblical passages. And what these three biblical passages have in common is that they affirm key doctrinal commitments, and they also talk about how to embody those doctrinal commitments through ritual.

So, for example, the tefillin ritual that I just spoke about a moment ago is mentioned in the Shema. The fringes ritual that I spoke about a moment ago was also mentioned in the Shema. So the Shema is also a ritual that only men are obligated, not women.

And so my way of thinking about what the Shema is in rabbinic tradition is, I see it as a way of taking the elite practice of Torah study, something that the, you know, more intellectually elite rabbis would be involved in, and taking it out to the laity. You don’t have to be able to study the entire Torah. You don’t have to be able to master the complexities of the Mishnah and the Talmud and the Midrash, all of these technical genres. All you need if you want to be a good rabbinic Jew, Joe Jew, is to be able to recite these key passages that are, I think, about embodying the covenantal commitment. Embodying oneself as a partner to God in the covenantal relationship. All you have to be able to do is recite these in the morning and in the evening. That is how Joe Jew becomes a good rabbinic, basically becomes equivalent to the elite rabbi.[11]

Emily: And if the goal of the Torah is coming closer into covenantal relationship with God, this seems like a very religious thing. So some listeners might assume that this religious law is a separate category from quote-unquote “real” law. It’s not Roman imperial law. It’s not Sassanian imperial law. But can we make this distinction between religious and non-religious laws when we’re talking about Rabbinics? Or are these categories actually intertwined?

Liz: Yeah, so I mean it’s a really interesting and complicated question. There’s no doubt about it.

So first of all, it’s a genre that does not match well, a hundred percent, with law. They certainly read like law in ways. They have aspects of them that sound like law. In other words, if you are X-and-X person, this is what you should do in X-and-X situation. So it’s certainly very prescriptive.

Another question that arises is that the genre includes a variety of topics. So you have materials that relate to what for the rabbis would have been contemporary ritual, like for example, reciting the Shema, wearing tefillin, wearing tzitzit, sitting in a sukkah (which is a little hut) in the fall festival of Sukkot, tabernacles. So you have some parts of the Mishnah, this prescriptive corpus that are very engaged in contemporary ritual.

You have other parts that are engaged in ritual that is no longer being practiced. So the rabbis emerge as a intellectual movement in the years and centuries following the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. The temple in Jerusalem was the focus of a lot of ritual activity, and the rabbis include extensive accounts of what should be done. And that’s in that same prescriptive mode, and it includes those same debates. You know well, Rabbi Meir says on one hand, versus Rabbi Yehuda who says on the other hand.

And then there’s another category of prescriptions that we might recognize as, more familiarly, quote “as law.” So there’s a section of the Mishnah, which is, which legislates about, let’s say civil damages. Your tree is hanging over my fence and drops figs. Do I have a right to eat those figs? [chuckles] Or do I not? Your ox kicked some stones while he was walking and that had an effect in, you know, something in my property. Those we would very much think of as civil law.

So on one hand, I would say that the Mishnah encompasses all of these topics in a single genre. It doesn’t distinguish in terms of the status. Each one of these arenas of life is submitted to a set of prescriptions that are authorized by the same principles. In other words, these are principles that are rooted in the Torah, the Hebrew Bible, principles that are rooted in rabbinic interpretation of those sources.

So on one hand, they’re part of a common corpus. On the other hand, even within, let’s say, a single tractate on a particular topic, you can go back and forth between laws that are applicable in the rabbinic era and laws that are not applicable because the temple has been destroyed.

I think in general the contemporary concept of law which is authorized by a political body, is a complicated fit for the Mishnah.

Rebekah: So, thinking about prescriptions that could be practiced in ancient Jewish life… Throughout history, many societies mark that transition to adulthood by women with the onset of menstruation. And for our listeners it sort of starts in Leviticus, right, where men are told to avoid their wives when they’re menstruating (Lev 18:20, 20:18). And women are considered ritually impure on their periods until they undergo a ritual bath.

Liz: [Interjecting] I just want to say, however, that Leviticus 15 to which you just alluded, which notes that women are impure when they are menstruating, also says that men are ritually impure when they have various genital secretions.

In fact, the treatment of men and women in Leviticus is comparable. The first half of Leviticus 15 talks about men’s irregular discharge, then it goes to men’s regular discharge, then there’s sort of a pivot point in the middle in which it talks about men and women having relations when she is on her period. So that means he has had a discharge and she’s on her period. And then it talks about women regular discharges. And then it concludes with women’s irregular discharges. So just to be clear, that’s a really sharp chiastic structure. And central to that chiastic structure is not a point of view that the impurity that is caused by women’s bleeding is uniquely female. There’s not a taboo. So I want to be really clear about that.

Rebekah: So the question I wanted to ask is, the rabbis are expanding on biblical texts like this text in Leviticus about menstruation and using them as sites of interpretation. So using ritual law around menstruation as an example, can you walk our audience through how the rabbis legislated around women’s bodies and what, if anything, these laws allow us to extract about real women?

Liz: First of all I want to make a sharp distinction between the way in which ritual purity was conceived biblically and the way in which the rabbis conceived and implemented it.

In the biblical material to which you alluded, first of all, men and women have equal ability to become ritually impure. And it’s relevant equally for each of them, for both men and for women. And the relevance shows up or is manifest in access to the temple and all of the sacred sites that are associated with the temple and the sacred utensils. So if one is ritually impure—whether by having a female secretion or having a male secretion or having some kind of skin disease or for having come into contact with the dead—the implications are you can’t have contact with the sacred space, sacred food, sacred implements. That is how this category operates in the biblical materials.

And as I noted, what’s significant about rabbinic ritual is that it’s taking place after the destruction of the temple. Which is to say, it doesn’t matter if you’re in a state of impurity because there is no sacred space to enter. There is no sacred food to touch by mistake. There is no sacred vessels to touch by mistake. So A, there’s no implications on that level, and B, it turns out that without a temple we are all impure because we can’t actually get to the temple to undergo the rituals that would allow us to enter the sacred space or touch the sacred items.

From the biblical perspective, post-temple, the laws of impurity that are derived from genital secretions are as irrelevant for men as they are for women. So Leviticus 15 is irrelevant. But Leviticus 18 remains relevant.

So what is Leviticus 18? Leviticus 18 is the first text that you referred to a moment ago. Leviticus 18 says a man should not have relations with a woman while she is in her period of impurity. What the whole rabbinic law—there I used the word law, right [all chuckle]—regulations, prescriptions around menstrual impurity, actually are not about legislating her coming into contact with the sacred. It’s rather about regulating her access and proximity to her husband. So that’s a huge shift.

The entire network of rabbinic prescriptions about menstruation are really oriented towards making sure that husbands and wives do not have sexual relations while a woman is menstruating. And the laws are talked about, are valorized, because precisely because they have this ability to quote create tension, sexual tension in the couple. You know what a great thing, wow, every month! Because it’s based on, the laws of menstrual purity, they don’t regulate contact and lack of contact with the sacred; they regulate intimacy and separation in the marital bed.

Emily: If the temple is no longer around, is there a way that we can read these texts against the grain to an extract any information about real women? Do we, do you think that real husbands and wives were practicing these distancing regulations every month while she was on her cycle? Or is this a fun rhetorical exercise of the rabbis sitting off in their libraries?

Liz: That’s a great question, were women practicing it? Were they annoyed?

The way in which the Talmud represents women is that they were leading the charge. Even you know a mustard seed’s worth of blood on the garment and they were like “Nope, I’m staying away!” And they, you know, took on some extra days of waiting before reunion. So that’s how holy the daughters of Israel were. That is one rabbinic representation.

So can we reconstruct women’s experience? That’s a really hard thing. An analogy that I sometimes give with my students is What can you learn about gender by going into the boys’ locker room in high school? You can learn a lot about guys posturing with other guys, one-upping, talking about women—in part because of how it represents them to the other guys. But no scholar in her right mind would try to reconstruct female sexuality based on what she heard in that locker room.

On some level, I think that the rabbis’ texts make women fairly inaccessible. We can learn a lot about gender. I think we learn about you know, male desires. Now, I don’t think that rabbis and women were adversaries. But insofar as the rabbis were trying to impose a ritual system on women who had their own experiences of their body—they were natives if you will. They were natives of the female body. So the rabbis, they might have made certain moves you know, “women would think they’re the ones who are the experts of their body. And so I’m going to create a system, a way to externalize what’s going on deep inside their bodies. And then I can be the expert.” So one very significant move that the rabbis make is, how do you tell when somebody is has begun menstruating? So, you know, I could just ask you, Emily, I could ask you, Rebekah, I won’t.

[all laugh]

Rebekah: I start craving chocolate! [laughs]

Liz: Exactly! So you have internal sensations. And it’s those sensations— Or, you know you’ve got a temper, you get mad at your family. So you have a variety of internal sensations that are accessible only to you, through immediate experience. So that’s one way to tell that a change is going on inside your body.

A different way is to create what Charlotte Fonrobert has called the quote “science of blood,” the set of external criteria.[12] Well, was it yellow? Was it green? Was it black? Was it red? And what kind of red is it? Is it the yellow of crocus or is the yellow of saffron? We’re going to call it “menstruating” if you meet criteria X, Y, and Z. Criteria X, Y, and Z are external. They are things that the rabbis can be experts in, in a way that no rabbi can ever be an expert on whether or not Rebekah is ready for her chocolate.

Rebekah: I was reading in the Babylonian Talmud, I think it’s Ketubot 72, where it has this whole discussion about whether or not a woman is legally trustworthy to report her own menstrual cycle to her husband. That was such a shocking thing to me, that a woman, as you said, knows her own body and then this idea that “Oh no, we can’t trust her [to] tell us what’s going on in her own body.”

Liz: Yeah.

Rebekah: So yeah, it’s an example of again that these are elite men who are writing these laws and that they tell us more about the men than their wives and daughters and yeah.

Liz: We have some capacity to speculate. So I think likewise you could say, well based on the rabbis’ need to create these external standards that are not based on the woman’s internal experience or innate experience of her body, we could speculate that women were practicing these laws, but maybe they were thinking about it in different terms.

So what’s contested is not “let’s do the laws or let’s not do the laws.” But what’s contested is, “Am I going to use this externalized set of criteria or am I just going to go with my gut?” I think that that is really a key issue for me. Is that, there are certain features. Just like I just sort of accept as a given that there’s a limitation to what we can reconstruct about females’ experience of their own bodies, there’s a limit to what we can reconstruct about female piety from these texts. I also accept that there’s a limit, you know. It’s like, they had certain stereotypes, social stereotypes. We can find it uncomfortable cause they don’t conform to our social stereotypes and our gender norms and our gender ideals.

Emily: Speaking of external criteria, the rabbinic discussion about witchcraft, something that originated in biblical laws like Exodus 22:17, the famous “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” Commenting on this passage the Babylonian Talmud asks why the Bible specifies witches rather than, say, warlocks or something male-coded. Why did it have to be women? And it gives an answer that most women are familiar with witchcraft (b. Sanhedrin 67a). Well, obviously!

Liz: Yeah.

Emily: I think this is Sanhedrin 67. So, how should we understand the rabbinic conversation about magic and its innate connection to women? What are some other ways that the rabbis might be othering women if that’s what’s happening in these texts?

Liz: So, the first thing I have to say is I am not 100% sure that what is going on here is that the rabbis are quote “othering women.”

Emily: Mmhm.

Liz: The Bible is filled with various prescriptions, and the Bible also includes prescriptions that are civil in nature and that are ritual in nature. And so it makes perfect sense that the rabbis who are inheriting this body of material and very devoted to it, that they also would mix those categories in the same way.

The prescriptive language of the Bible is Hebrew. And in Hebrew, in classical and modern Hebrew, there’s no such thing as an ungendered noun, an ungendered verb, an ungendered adjective. Now there’s ways that you can create gender neutral prescriptions. One way is to say “this prescription is incumbent upon men and women.” So that’s what I call gender inclusive. Another approach is to use a term that I would say is grammatically gendered but is semantically gender neutral. So for example, the word adam is “person.” It’s grammatically masculine. So you’re still going to have grammatical gender, but the semantic value of the word adam is to be gender neutral.

Now, the portion of Exodus that you are citing, “You shall not let a witch live,” is a portion of the Bible that tends to use the default masculine. So that section of Exodus is filled with materials that are articulated using grammatically masculine forms. And this leads to a whole set of questions on the part of the rabbis. Every time they encounter one of these grammatically masculine forms, they’re basically doing an investigation of grammatical gender: is grammatical gender significant or not?

And so one of the things that they are observing is that they’re saying, “yes, grammatical gender is significant.” Whenever it says ish, oftentimes that actually means not just grammatically masculine but gender inclusive, but it actually means grammatically masculine and socially masculine. In other words, not just a grammatical figure, it is meaningfully masculine.

That is a project that runs all across biblical, rabbinic interpretation of biblical legal materials. And I think that this interpretation that you’re citing here is an instance of the rabbis paying attention to the exact same thing. How do we make sense of this thing that is deliberately constructed as female? And what I think is fascinating is that the rabbis actually say, “Oh no this is a gender inclusive use of the feminine. This is not a reference to women only. Who should you not let live? Is it only female witches? No for sure or not! Of course you should also apply the same prescription to male witches that you apply to female witches. Absolutely!” So if this is a case of a gender inclusive law, then we need to ask “Well, why did the Bible use feminine language?” And so the answer that the rabbis give is, “Well, you know, it’s the way of women. You know women are associated with witches, and so that so essentially what the biblical language was doing was accommodating them, accommodating that general sensibility.”

What I see going on here actually is in certain ways the rabbis like, “Oh, this is just so cool! There’s female language here! What do we make of that?!”

Emily: But the reason they find is still an idea that women are connected with witchcraft or witchery in some way. So there’s still—

Liz: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely so yeah. Yes, women are connected with witchcraft; that’s their social norm.

There’s another instance where we see the rabbis sort of making a gesture to social norms in their interpretation of this kind of this language issue. So there’s a verse in Leviticus 19: “Ish aviv veaviv tirau” (Lev 19:3) “A man,” this is an address to the subject, “yee,” you in the plural, “shall revere” both “his father and his mother.” Now the pronouns here are really off the wall because we’ve got plural, we’ve got singular, we’ve got second person, we’ve got third person. So the law is addressed initially to the third person ish. You know a man should not do X, Y, and Z. He should revere his mother and father. At the same time, the final verb which is the prescriptive moment says you plural shall fear. So it is both plural, whereas the first subject is singular; and it’s in the second person, as opposed to the third person. So the pronouns are very confusing.

And this is similar to the question that they ask about mekashefah (Exod 22:18), about the feminine form of witch. So now they have to go back and say, “Well, wait a minute. If the law includes both men and women, then why did it use the masculine form?” Now this is exactly the same question that they asked about the witch. If the law includes both male witches and female witches, why did the scripture use the language of a female witch? “Ehhhh, it was accommodating the way things are in the world. It was accommodating social sensibilities.”

So they do the same thing here in the case of revering your parents. It says a man should, you guys should, fear your mother and father. Does this include both males and females? Absolutely. Well if it includes both males and females, why does it say ish explicitly? Why does it use that male language? The reason it uses that male language is because it is the way of the world that men have the capacity, they have the social position, to be able to address their parents’ needs more directly cause they’re in social control with themselves. Whereas women, because they are in their husbands’ households, have much less control over their time and their space and their fiscal resources. Therefore, they don’t have access, and so that’s why it says ish. That’s why it says “a man.”

And so I see both of these examples as comparable. In both cases, even though both men and women fall under the rubric of the prescription, scripture is gendered nonetheless. Whether it’s the female word for witch or the male word for the person who should honor their mother and father. And what the rabbis are doing is they’re saying, sometimes scripture genders things not because of legal consequences but as a reflection of how human society conducts itself.

So I’m continuing to resist you on some level. Yes, it’s true, the way that society conducts itself the way you know what they’re taking for granted here in terms of their social norms are that witchcraft is associated with women, and they’re taking for granted that women don’t have full control over their economic and spatial and temporal resources.

Emily: It is especially difficult—we might say impossible—to read women into ancient rabbinic literature. But scholar Tal Ilan has argued that historical inquiry into the lives of Jewish women in this period is equally as justified as other historical projects that don’t have much evidence, like the Lost Island of Roanoke.[13] [laughs] And that has occupied numerous Colonial historians even though we don’t have much to go on!

So keeping this tension in mind, what are some of the main strategies that readers of rabbinic law have used to find the voices of women or look for the voices of women?

Liz: So I think there’s different ways to think about this. As I said, when we were talking about the menstrual material, menstrual purity materials, I think that one strategy is when you’re looking for some kind of the perspective of women, is by seeing where the rabbis are pushing. And envisioning maybe that there’s some real woman there who’s pushing back, and that’s why they’ve pushed in the way that they’ve pushed.

To be honest, I mean, and maybe you’ve gathered this already through the course of our conversation, I’m not super optimistic about reconstructing women’s experience from rabbinic materials. I think that they tell us a lot about rabbinic views of gender but very little about women’s experience—whether women experience of gender or women’s experience of other things.

So for me the most compelling approach is to go to places where we can get direct evidence about ancient Jewish women.

So I happen to be a huge fan of the Babatha archive, which is a package of documents in a satchel by a woman named Babatha bat Shim’on, “Babatha daughter of Simon.” And her documents were found along with a ball of yarn, so a personal item, a shoe, a sandal. And they were found in this cave that is associated with the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

During this period where there was like a bunch of, a small group of Jewish vigilantes led by Bar Kochba against the Roman Empire. It’s sort of like a revolt akin to the revolt, sometimes called the Second Revolt, the revolt that was akin to the one that ended in the destruction of the temple. And for a very short period Bar Kokhba was a, sort of had a military success in terms of pushing the Romans out, and they even minted some coins. So there was a limited kind of Jewish independence in the land of Judea around 132 [CE]. But it was a very tumultuous and perilous time, as well.

And so there’s this cave in the Judean desert where, it’s called the Cave of Letters. And they found letters between Bar Kokhba and one of his top generals. What we also have is this satchel of documents that this woman, a refugee; I mean here we are again in a time of incredible political upheaval. Individuals being uprooted. She was probably from the southern part of Judea around Nabataea, down the bottom of the Dead Sea. And we find her documents up in this cave which is midway up the Dead Sea. So she’s a good number of kilometers from home, visiting probably her daughter-in-law. And she gets caught up. And she ends up in this cave.

And because it’s wartime, you know, what is— We see the Ukrainians, they’re all bringing their dogs with them. That’s like the big thing, right? They want that which is dear and near and important to them. So Babatha also took what was near and dear to her. She was in the middle of some legal issues around custody and maintenance of her son. And there was some legal battles. So she took those legal documents. She had inherited from her dad a date orchard, but there was some confusion as to whether or not his rights were 100% on that. So she had the documents related to that.

So we see in this bundle we see an extraordinarily courageous woman who is like going into a war zone. Who is probably a businesswoman because she’s got this stuff related to her orchard. She’s really concerned about managing the finances of her son. The boy’s father has died, and she doesn’t feel good about how the court-appointed people who are taking care of the finances have been managing things. I see there, like if I want to go try to reconstruct women from the time of the Mishnah, I find it, I find that so much more exciting.

Emily: Well, Liz, this has been so wonderful. But before we wrap up we are wondering what’s your favorite rabbinic discussion that relates to women? And why does it resonate with you so much? [laughs]

Liz: Okay I was hoping you were going to ask that question. In the commentary on Berakhot — “Mi shemeto mutal lefanayv” (מי שמתו מוטל לפניו) (Mishnah Berakhot 3:1)[14] Okay, so somebody whose dead person is still unburied. So you are alive, and your close relative just died. You haven’t yet buried that person. So the deceased remains unburied. You are exempt from reciting Shema, wearing tefillin, and doing a bunch of other positive commandments in the Torah.

And you can ask, well, why are you exempt from reciting the Shema? The Gemara offers, the Torah offers, is that it’s out of concern of the feelings of the deceased. In other words, if the deceased sees you, senses you wearing tefillin, saying the Shema, doing these commandments, dedicating your body, your life, your vitality to covenantal commitment, they are going to be hurt. They’re going to feel like you are mocking.

What ensues in the Talmud is a discussion: “Well, can the dead really perceive what’s going on?” And they bring a variety of vignettes to and, you know, and some textual interpretation, biblical interpretation, to support their view. And my favorite story featuring a woman is part of this response.

So, yes, the Gemara says the dead do know what’s going on because we have this story about Zeiri. And he had deposited some coins with his landlady. He went to the House of Rav. He hung out there for a little while. While he was hanging out, the landlady died. He’s like “Oy gevalt! What am I gonna do? My coins? My coins! Oh no my money right?” [all laugh] So he goes to the cemetery. He does what any rational person would do in his position: He goes to the cemetery and he says, “Listen, where are my coins?” And she says where they are. We’ve solved the Gemara question. Yes, the dead can communicate. They know what’s going on.

But the story doesn’t stop there. The story continues. The dead landlady is like, “Don’t go yet. As long as I’m talking to you, as long as I have your attention, can you please tell Ma that there’s another lady who’s coming tomorrow.” She’s dying tomorrow. “Can you please send my eye makeup and my comb with her?”

Just want to stop there. Like what is that about? So first of all, it’s not necessary for the Talmud’s argumentation. Second of all, it is so incredibly female. She’s dead. She’s got emotional vulnerability. Maybe she’s starting to decompose. She wants her comb and her eye makeup. I mean, I spent years like fascinated with this lady. I finally figured out for myself what I can learn from her. But I was like okay, yeah, is there something to write a feminist commentary to the Babylonian Talmud about? Yes, absolutely.

[podcast musical interlude]

Emily: To a twenty-first century listener, this world of religious legal rulings might seem incredibly foreign and strange. But religious law actually has a long and enduring legacy. For instance, Massachusetts’ first published legal code The Body of Liberties (c. 1630) cited the Bible, rather than Common Law, to support capital punishment. The crime of witchcraft was punishable by death until 1750, only a few decades before Abigail Adams asked her husband to “remember the ladies.”[15] And even after that, the last public witch trial in America still convened a full century later, on May 14, 1878–ironically in Salem, Massachusetts.[16]

Rebekah: In Europe and America, one popular test for witchery from the ninth through seventeenth centuries was the swim test, where a suspected witch was thrown into a body of water. If she sank and drowned, tragically she had been innocent. If she floated, she was a witch and would be summarily executed.[17] The supposed “test” was a set-up, designed to prove she was the dangerous Other that her accusers claimed.

Emily: Remember Beruriah? The woman who issued her own rabbinic rulings and got shut down? Writing in the 11th century, the famous French rabbi Rashi re-edited Beruriah’s story and turned it into a similarly rigged “trial.”

Rashi characterized her as infringing on the rabbinic boys’ club: she challenged the Talmudic ruling that said women were weaker-willed in matters of the flesh. In Rashi’s medieval revision, Beruriah’s husband ordered one of his students to seduce her to affirm the Talmud. She succumbed. And when she realized it was all a set-up, she committed suicide (Rashi on Avodah Zarah 18b:5).[18] Scholar Daniel Boyarin suggests that Rashi’s story may reflect an attempt to shore up a Mishnaic claim that female nature was fundamentally incompatible with Torah study (m.Sotah 3:4).[19] Providing so-called “evidence” through an invented story of women’s innate susceptibility, Beruriah (and through her, all women) are essentialized. In the end, just like the medieval women accused of witchcraft, Beruriah loses her life.

Rebekah: Today’s episode isn’t about the roots of witchcraft laws in religious tradition, or even entirely about recovering the real women behind the witches – because we all know now how complicated a mission that is.

It’s about suffering the “witches” to live. We’re using “witch” as a cipher. It’s not a word we love. But it’s a poignant stand-in for all the stereotypes and literary constructions we have to contend with in ancient literature. Women were light-headed. Women were the devil’s gateway. Women were dangerous. And the very existence of the label and rabbinic chastisements of women remind us that there were women in that world to be chastised. We suffer the word “witch” to live so as not to erase our foremothers even further from the story.

Emily: We can’t recover all the real women behind the witches, but we acknowledge that they were there. The menstruating women who could measure their own cycles, thank you very much. Who had names and faces and hopes and dreams, even if we don’t know them today.

Some sages did make inclusive choices in their interpretations and directed laws to both men and women. As Liz put it, men could be witches too! And sometimes non-literary evidence gives us a window into the lives of those actual women who lived in the world of the rabbis. The women like Babatha, who was a businesswoman and property owner. Or those like Rufina, leading her synagogue as an archisynagogos.

Rebekah: Some rabbis did not trust women to make decisions for themselves, or to tell the truth about their menstrual cycles, or to study the Torah faithfully. Their bodies, their brains, and their self-control were all suspect. Women became flattened constructs held at a safe and controlled distance from the men. So, let’s suffer our witches to live, in memoriam for the ones we’ll never know.

[podcast theme music plays over outro]

Rebekah: If you enjoyed our show, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, or wherever you get your podcasts. Visit us at womenwhowentbefore.com or on Twitter @womenbefore.

This podcast is written, produced, and edited by us, Rebekah Haigh and Emily Chesley. This episode was fact-checked by Eliav Grossman. Our music was composed and produced by Moses Sun. The podcast is sponsored by the Center for Culture, Society and Religion, the Program in Judaic Studies, and the Stanley J. Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies all at Princeton University.

Emily: Thanks for listening to Women Who Went Before. And don’t forget:

Both: Women were there!

[podcast music bounces to its end]

[1] Erin Allen, “Remember the Ladies,” Library of Congress Blog, March 31, 2016.

[2] Bernadette J. Brooten, “Inscriptional Evidence for Women as Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue,” Society of Biblical Literature: 1981 Seminar Papers, vol. 20, ed. Kent Harold Richards (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1981), 1–17.

[3] Bernadette Brooten makes this point in Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue (Chico, CA; 1982); see also Elizabeth Shanks Alexander’s summary and analysis in “The Impact of Feminism on Rabbinic Studies: The Impossible Paradox of Reading Women into Rabbinic Literature,” in Jews and Gender: The Challenge to Hierarchy, ed. Jonathan Frankel Studies (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 112–113.

[4] “There are, however, a number of letters from the Old Babylonian, Middle Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian periods that deal with cases where witchcraft accusations were publicly made against specific people and resulted in legal proceedings. The accusations arise within small social circles, usually within one (extended) family or village. They are regularly embedded in preexisting conflicts and concern persons who have been isolated within their social group. In all cases so far known, the accused persons are women, a fact that agrees with the primarily female characterization of the witch in the stereotypes found in the incantations and prayers of the anti-witchcraft rituals.” Tzvi Abusch and Daniel Schwemer, Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals (Leiden: Brill, 17 Dec. 2010), 7.

[5] Tal Ilan, Silencing the Queen: The Literary Histories of Shelamzion and Other Jewish Women (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 214–258 (esp. 222–223); and Rebecca Lesses, “'The Most Worthy of Women is a Mistress of Magic': Women as Witches and Ritual Practitioners in 1 Enoch and Rabbinic Sources,” in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World, eds. Kimberly B. Stratton and Dayna S. Kalleres (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 71–107.

[6] Daniel Ogden, Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts In the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 78.

[7] It’s an example of how earlier or less-authoritative rabbinic traditions dealing with women in were intentionally (or unintentionally) censored by later interpreters and traditions. See, Ṭal Ilan, Mine and Yours Are Hers: Retrieving Women’s History From Rabbinic Literature (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 51–60.

[8] On the Rabbinic permutations of Beruriah, see Tal Ilan, Integrating Women into Second Temple History (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1999), 175–194.

[9] See also the discussion about Michal, daughter of King Saul, who reportedly wore tefillin: b. Erubin 96b and p. Erubin 59a. References courtesy of Eliav Grossman.

[10] Elizabeth Shanks Alexander, Gender and Timebound Commandments in Judaism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) i.

[11] For more on these connections, see Elizabeth Shanks Alexander, “Women’s Exemption from Shema and Tefillin and How these Rituals Came be Viewed as Torah Study,” Journal for the Study of Judaism 42 (2011): 531–579.

[12] See Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert, Menstrual Purity: Rabbinic and Christian Reconstructions of Biblical Gender (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000).

[13] Ilan, Integrating Women; and Tal Ilan, Mine and Yours Are Hers: Retrieving Women’s History From Rabbinic Literature (Leiden: Brill, 1997).

[14] Elizabeth Shanks Alexander, “When the Dead Want to Primp: Talmudic Gender as Theological Prompt · BT Berakhot 18b.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 28 (2015): 120–33.

[15] “Witches and Witchcraft: The First Person Executed in the Colonies,” State of Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Library Services, no date.

[16] Gordon Harris, “Lucretia Brown and the last witchcraft trial in America, May 14, 1878,” Historic Ipswich, https://historicipswich.org/2021/01/02/lucretia-brown-and-the-last-witchcraft-trial-in-america. See also an exhibition in Fall 2022 at the New York Historical Society on “The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming.”

[17] Nathan Dorn, “Swimming a Witch: Evidence in 17th-century English Witchcraft Trials,” In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress, February 8, 2022.

[18] See Naomi Cohen, “Bruria in the Bavli and in Rashi ‘Avodah Zarah’ 18B.” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 48, no. 2/3 (2015): 29–40.

[19] Daniel Boyarin, Carnal Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture, The New Historicism: Studies in Cultural Poetics (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995, originally published 1993), 204–211 and 202n20; and Brenda Socachevsky Bacon, “Reader Response: How Shall We Tell the Story of Beruriah’s End?” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 5 (2002): 231–39.

-

Tzvi Abusch and Daniel Schwemer. Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Elizabeth Shanks Alexander. “Businesswomen Before Bar Kokhba,” Jewish Review of Books 8, no. 3 (2017): 7–8. Review of Babatha’s Orchard: The Yadin Papyri and an Ancient Jewish Family Tale Retold by Philip F. Elser.

______. Gender and Timebound Commandments in Judaism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

______. “The Impact of Feminism on Rabbinic Studies: The Impossible Paradox of Reading Women into Rabbinic Literature.” Pp. 101–118 in Jews and Gender: The Challenge to Hierarchy. Edited by Jonathan Frankel. Oxford: 2000.

______. “Reading for Gender in Ancient Jewish Biblical Interpretation: The Damascus Document and Mekilta of R. Ishmael.” Pp. 15-33 in The Faces of Torah: Studies in the Texts and Contexts of Ancient Judaism in Honor of Steven Fraade. Journal of Ancient Judaism. Supplements. Volume 22. Edited by Christine Hayes, Tzvi Novick and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017.

______. "When the Dead Want to Primp: Talmudic Gender as Theological Prompt · BT Berakhot 18b.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 28 (2015): 120–33.

______. “Women’s Exemption from Shema and Tefillin and How These Rituals Came to Be Viewed as Torah Study.” Journal for the study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman period 42, no. 4-5 (2011): 531–579.

Erin Allen. “Remember the Ladies.” Library of Congress Blog. March 31, 2016.

Brenda Socachevsky Bacon, “Reader Response: How Shall We Tell the Story of Beruriah’s End?” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 5 (2002): 231–39.

Daniel Boyarin. Carnal Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture. The New Historicism: Studies in Cultural Poetics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995, originally published 1993.

Bernadette J. Brooten. “Inscriptional Evidence for Women as Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue.” Society of Biblical Literature: 1981 Seminar Papers. Volume 20. Edited by Kent Harold Richards. Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1981.

______. Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue. Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1982. Digital edition: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvzpv5mr.

Naomi Cohen. “Bruria in the Bavli and in Rashi ‘Avodah Zarah’ 18B.” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 48, no. 2/3 (2015): 29–40.

Nathan Dorn. “Swimming a Witch: Evidence in 17th-century English Witchcraft Trials.” In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress, February 8, 2022.

Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert. Menstrual Purity: Rabbinic and Christian Reconstructions of Biblical Gender. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Gordon Harris. “Lucretia Brown and the last witchcraft trial in America, May 14, 1878.” Historic Ipswich. https://historicipswich.org/2021/01/02/lucretia-brown-and-the-last-witchcraft-trial-in-america/.

Tal Ilan. Integrating Women Into Second Temple History. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999.

______. Mine and Yours Are Hers: Retrieving Women’s History From Rabbinic Literature. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

______. Silencing the Queen: The Literary Histories of Shelamzion and Other Jewish Women. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006.

Rebecca Lesses. “’The Most Worthy of Women is a Mistress of Magic’: Women as Witches and Ritual Practitioners in 1 Enoch and Rabbinic Sources.” Pp. 71–107 in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World. Edited by Kimberly B. Stratton and Dayna S. Kalleres. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Daniel Ogden. Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts In the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

"Witches and Witchcraft: The First Person Executed in the Colonies.” State of Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Library Services. No date.

Episode Cover Art

This marble funerary plaque gives us the name of Sophia, who was an archisynagogissa – literally, “the head of a synagogue” – in the town of Kissamos on Crete. Rare discoveries like this challenge the narrative in male-authored Rabbinic texts that women could not study Torah.

Credit: Funerary plaque of archisynagogissa Sophia. 4th or 5th century CE. Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania-Archaeological Museum of Kissamos, inventory number E16. Exhibited in the Jewish Museum of Greece. Photograph by Emily Chesley.

Women Who Went Before is written, produced, and edited by Rebekah Haigh and Emily Chesley. The music is composed and produced by Moses Sun.

Sponsored by the Center for Culture, Society, and Religion, the Program in Judaic Studies, and the Stanley J. Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton University

Views expressed on the podcast are solely those of the individuals, and do not represent Princeton University.